LESSON 22: TECHNOCRACY: THE DESIGN

In the preceding lessons we learned that the events occurring the earth are events of matter and energy, and that they are limited by the fundamental properties of matter and energy. In addition to this we have noted some of the more important characteristics peculiar to organisms, and singling out one particular species, man, we have followed its rise to supremacy during the past several thousands of years.

We have observed that this rise of the human species and corresponding adjustments, both up and down, of the other species or organisms, have been due almost entirely to the fact that the human species has progressively accumulated new and superior techniques by which a progressively larger share of the available energy could be converted to its uses.

We have seen that notwithstanding the fact that this progression has been slowly under way since times prior to the records of written history, the greater part of this advance, in actual physical magnitude, has occurred since the year 1900, or within the lifetime of nearly one-half of our present population.

It is due to the progress of these last few decades, that for the first time in human history, whole populations in certain geographical areas have changed over from a primary dependence upon agriculture for a livelihood to a primary dependence upon a technological mechanism, constructed principally from metals obtained from the minerals of the earth, and operated in the main from the energy contained in fossil fuels preserved within the earth.

Hence, this technological development has come to be localized in those geographical areas most abundantly supplied with the essential industrial minerals, such as the ores of iron, copper, tin, lead, zinc, etc., and the fossil fuels, coal, and oil. We have observed further that the Continent of North America ranks first among all the areas of the earth in its supply of these essential minerals, with western Europe second. Consequently, this technological development has reached its greatest heights in the areas bounding the North Atlantic with the production or rate of conversion of extraneous energy per capita having reached a far greater advancement in North America than in Europe.

The Arrival of Technology. We have also reviewed some of the paradoxes and the problems that have arisen in North America due to the conflict between the physical realities of this technological mechanism, and the social customs and folkways handed down from countless ages of low-energy agrarian civilizations.

It is to the problem of the elimination of this conflict that we now turn our attention, but before proceeding further let us get it entirely clear as to just what the conflict is.

In the past we operated more or less as independent productive units. The industry of the whole population was agriculture and small-scale, handicraft manufacturing. The interdependence among separate productive units was slight, or they were so loosely coupled that the opening up or shutting down of one unit was of slight consequence to the others. This was because any given essential product was not produced by one or two large establishments, but by innumerable small ones. The total output of that product was the statistical result of all the operations of all the separate, small establishments. Consequently, the effect of the opening or closing of any single establishment was negligibly small as compared with the total output of all establishments. The probability that a large fraction of all establishments of the same kind would open and close in unison was also negligibly small.

In the past, human labor, while not always the sole source of power, was so essential a part of the productive process that, in general, a decrease in the rate of production only took place when there was also an increase in the number of manhours of human labor expended. During periods in which there was no technological improvement this relationship between production and man-hours was one of strict proportionality.

In the past there was individual ownership of small units, so that the exchange of goods on a barter or simple, hard-money basis resulted in a stable operation of the productive mechanism. Individual wealth could be, and was acquired, in recompense for diligence, thrift, and hard labor. Those were the days of the spade, the wooden plow, homemade clothing, the ox-cart, and more recently, the horse and buggy. Today, all that has changed.

As time progressed, the population grew and the production increased. Productive units which began as small handicraft units were enlarged; new ones were established; some of the old ones dropped out. The average rate of output per establishment became so great that the total number of establishments of each given kind required for the total production, began to decrease, until today, for a large number of essential products, only a dozen or so establishments can produce at a rate equal to the consuming capacity of the entire population. In some instances, one single plant at full load operation can produce at such a rate.

While this trend has advanced further in some industries than in others, it is present in all industries, including even the most backward of them— agriculture. Since the cause for this development, namely, technological improvements, still exists in full force, there can be no doubt that this trend will be continued into the future.

When, however, all products of a given kind come to be produced, as is the case today, by only a small number of productive establishments, under the ownership and control of even a smaller number of corporate bodies, and when the financial restrictions that bear upon the one bear also upon the others, the probability that all will increase or decrease production in unison with the amplitude of the oscillations approaching that from capacity output to complete shutdown, amounts almost to a certainty.

Since the amount consumed over a period of a few years is, in general, equal to or less than the amount produced in that time, these oscillations in the productive process, and the forced restrictions upon production, can only result in a restriction and curtailment of consumption on the part of the public. When this curtailment becomes so severe as to amount to privation on the part of a large proportion of the population, the controls causing the restricted production will have long since passed their period of social usefulness and will be rapidly approaching the limits of social tolerance.

In the present, as contrasted with the past, the great majority of the population is in a position of absolute dependence upon the uninterrupted operation of a technological mechanism. In the United States today, there are approximately 30 million people who live directly upon the soil, whereas almost 100 million people live in towns and cities. These latter are strictly dependent for food, water, clothing, shelter, heat, transportation, and communications, upon the uninterrupted operation of the railways, the power plants, the telephone and telegraph systems, the mines, factories, farms, etc. Even the farmer of today would be in dire straits were his gasoline supply, his coal, his factory-built tools, his store-bought clothing, and even his canned foods not forthcoming.

In all preceding human history, until within the last two decades, an increase in production was accompanied by an increase in the man-hours of human labor; today, we have reached the stage where an increase of production is accompanied by a decrease in man-hours.

This is due to the facts that the motive power of present industrial equipment has become almost exclusively kilowatt-hours of extraneous energy, and that we have learned that in repetitive processes it is always possible to build a machine that will perform the given function with greater speed and precision, and at lower unit cost than it is physically possible for any human being to do.

Every time new equipment is devised, or old equipment redesigned, the newer operates in general, faster, and more automatically than its predecessor, and since, as yet the accomplishments in this direction are small compared with the possibilities, it is certain that this trend will continue also into the future.

In the remote past, the rates of increase of population and production were negligibly small; in the recent past the rates of growth of both population and production have been the greatest the world has ever known; in the present and the future the rates of growth of both population and industrial production will approach zero as the leveling-off process continues.

In the past, when man-hours of human labor formed an essential part of wealth production, it was possible to effect a socially tolerable distribution of the product by means of a monetary payment on the basis of the hours of labor expended in the productive procedure.

At the present and in the future, since the hours of labor in the productive processes have already become unimportant, and shall become increasingly less important with time, any distribution of an abundance of production, based upon the man-hours of human participation can only lead to a failure of the distributive mechanism and industrial stagnation.

The Trends. Now it is this complex of circumstances that forms the basis of our problem and also of its solution. We have the North American Continent with its unequaled natural resources. We have on this Continent a population that is more nearly homogeneous than that of any other Continent. This population has already designed, built, and now operates the largest and most complex array of technological equipment the world has ever seen. Furthermore, this population has a higher percentage of technically trained personnel than any major population that has ever existed. It has the highest average consumption of extraneous energy per capita the world has ever known. Its resources exist in such abundance, that there need be no insurmountable restriction on the standard of living due to resource exhaustion, at least into the somewhat distant future.

Now the analysis that we have made shows that while both production and population are leveling off to a maximum, the physical maximum of production will be set by the maximum physical capacity of the public to consume, which contrary to the credo of the economists, is definitely limited and finite.

We have also seen that it is only possible to approach that maximum by a continuation of the processes that now so markedly differentiate our present from the past, that is, by an increased substitution of kilowatt-hours for man-hours; by a continuous technological improvement of our equipment towards greater efficiency and automaticity; by a continued integration of our productive equipment from smaller into larger units and under unit control and operation; and by an improvement of the operating load factor, approaching the ultimate limit of 100 percent.

These are the trends and there is no possible way of reversing them. Since each has its own limits—essentially those stated above—it follows that in time we shall approach those limits. But as and when we do approach them, the very requirements of the operation of our industrial equipment will dictate a directional control and a social organization designed especially to meet these particular needs.

From such a state of operation the unavoidable by-products will be the smallest amount of human labor per capita, the highest physical standard of living, the highest standard of public health and social security any of the world’s populations have ever known.

The Solution. The above is our social progression and the goal is almost reached. Whether we as individuals, may prefer that goal or some other is irrelevant, since we are dealing with a progression that is beyond our individual or collective abilities to arrest. Since this progression unavoidably conflicts with our horse and buggy ideologies and folkways, it is not to be found surprising that restrictive and impeding measures are attempted; but as to the final outcome one has only to recall the similar restrictive measures that were attempted with respect to the introduction of the use of the bathtub and of automobiles as well as with respect to most of the other major innovations of the past. Invariably the old ideologies of the past go, and new ones conforming more nearly to the new physical factors, take their places.

The conflict that we are now in the midst of is precisely of this sort—a conflict between physical reality and the antiquated ideology of a bygone age. In the case of the automobile, the ultimate solution came by abandoning the attempts at suppression and by devising control measures to fit the physical requirements of the thing being installed. Since the horse and buggy was physically different from the automobile, it is obvious that traffic measures and road design adequate for the former would be inadequate for the latter and no solution was possible which was not formulated in recognition of this fact.

So today, with the operation of our technological mechanism, the control measures that must and will be adopted are those that most nearly conform to the technological operating requirements of that mechanism.

These requirements can only be known by those who are intimately familiar with the technical details of that mechanism our technically trained personnel; though prior to there being a general recognition of this fact, we may expect to witness performances on the part of our educators, economists, sociologists, lawyers, politicians, and businessmen that will parallel the performances of all the witch doctors of preceding ages.

It was a recognition of the fact that we are confronted with a technological problem which requires a technological solution, that prompted the scientists and technologists who later organized Technocracy Inc. to begin the study of the problem and its solution as early as the year 1919.

Out of that study a technological design expressly for the purpose of meeting this technological problem has been produced. An outline of some of its principle features are presented in what follows.

Personnel. First, required resources must be available; second, the industrial equipment must exist; and third, the population must be so trained and organized as to maintain the continuance of the operation within the limits specified.

This brings us to the question of the design of the social organization. To begin with, let us recall that the population falls into three social classes as regards their ability to do service. The first is composed of those who, because of their youthfulness, have not yet begun their service. This includes the period from infancy up through all stages of formal education. After this period comes the second, during which the individual performs a social service at some function or other. Finally, the last period is that of retirement, which extends from the end of the period of service until the death of the individual. These three periods embrace the activities of all normal individuals. There is always another smaller group which, because of ill-health, or some other form of incapacitation, is not performing any useful social service at a time when it normally would be.

The social organization, therefore, must embrace all those of both sexes who are not exempt from the performance of some useful function because of belonging to one of the other groups. Let it be emphasized that these groups of a population are not something new but are groups that exist in any society. The chief difference is that in this case we have deliberately left out certain groups which ordinarily exist, namely those who perform no useful social service though able to do so, and those whose services are definitely socially objectionable. It is the group which is giving service at some socially useful function which constitutes the personnel of our operating organization.

What must this organization do?

It must operate the entire physical equipment of the North American Continent. It must perform all service functions, such as public health service, education, recreation, etc., for the population of this entire area. In other words, it has to man every job that exists.

What other properties must this organization have?

It must see to it that the right man is in the right place. This depends both upon the technical qualification of the individual as compared with the corresponding requirements of the job, and also upon the biological factors of the human animal discussed previously. It must see to it that the man who is in the position to give orders to other men must be the type who, in an uncontrolled situation, would spontaneously assume that position among his fellows. There must be as far as possible no inversion of the natural ‘peck-rights’ among the men.

It must provide ample leeway for the expression of individual initiative on the part of those gifted with such modes of behavior, so long as such expression of individual initiative does not occur in modes of action which are themselves socially objectionable. It must be dynamic rather than static. This is to say, the operations themselves must be allowed to undergo a normal progressive evolution, including an evolution in the industrial equipment, and the organization structure must likewise evolve to whatever extent becomes necessary.

The general form of the organization is dictated by the functions which must be performed. Thus, there is a direct functional relationship between the conductor and the engineer on a railway train, whereas there is no functional relationship whatever between the members-at-large of a political or religious organization. The major divisions of this organization, therefore, would be automatically determined by the major divisions of the functions that must be performed. The general function of communications, for instance—mail, telegraph, telephone, and radio— automatically constitutes a functional unit.

Operating Example. Lest the above specifications of a functional organization tend to frighten one, let us look about at some of the functional organizations which exist already. One of the largest single functional organizations existing at the present time is that of the Bell Telephone system. What we mean particularly here is that branch of the Bell system personnel that designs, constructs, installs, maintains, and operates the physical equipment of the system. The financial superstructure—the stock and bond holders, the board of directors, the president of the company, and other similar officials whose duties are chiefly financial, are distinctly not a part of this functional organization, and technically their services could readily be dispensed with. This functional organization comprises upwards of 300,000 people. It is of interest to review what its performance is, and something of its internal structure, since relationships which obtain in organizations of this immensity will undoubtedly likewise obtain in the greater organization whose design we are anticipating.

What are the characteristics of this telephone organization?

- It maintains in continuous operation what is probably the most complex single sequence array of physical apparatus in existence.

- It is dynamic in that it is continually changing the apparatus with which it has to deal, and remolding the organization accordingly. Here we have a single organization which came into existence as a mere handful of men in the 1880’s. Starting initially with no equipment, it has designed, built, and installed equipment, and replaced this with still newer equipment, until now it spans as a single network most of the North American Continent, and maintains interconnecting long-distance service to almost all parts of the world. All this has been done with rarely an interruption of 24 hours per day service to the individual subscriber. The organization itself has grown in the meantime from zero to 300,000 people.

- That somehow or other the right man must have been placed in the right job is sufficiently attested by the fact that the system works. The fact that an individual on any one telephone in a given city can call any other telephone in that city at any hour of the day or night, and in all kinds of weather, with only a few seconds of delay, or that a long-distance call can be completed in a similar manner completely across the Continent in a mere matter of a minute or two, is ample evidence that the individuals in whatever capacity, in the functional operation of the telephone system must be competent to handle their jobs.

Thus, we see that this functional organization, comprising 300,000 people, satisfies a number of the basic requirements of the organization whose design we contemplate. It is worthwhile, therefore, to examine somewhat the internal structure of this organization.

What is the method whereby the right man is found for the right place? What is the basis on which it is decided that a telephone circuit will be according to one wiring diagram and not according to another?

The fitting of the man to the job is not done by election or by any of the familiar democratic or political procedures. The man gets his job by appointment, and he is promoted or demoted also by appointment. The people making the appointment are invariably those who are familiar both with the technical requirements of the job and with the technical qualifications of the man. An error of appointment invariably shows up in the inability of the appointee to hold the job, but such errors can promptly be corrected by demotion or transfer until the man finds a job which he can perform. This appointive system pyramids on up through the ranks of all functional sub-divisions of the system, and even the chief engineers and the operating vice-presidents attain and hold their positions likewise by appointment. It is here that the functional organization comes to the apex of its pyramid and ends, and where the financial superstructure begins. At this point also the criteria of performance suddenly change. In the functional sequence the criterion of performance is how well the telephone system works. In the financial superstructure the criterion of performance is the amount of dividends paid to the stockholders. Even the personnel of the latter are not the free agents they are commonly presumed to be, because if the dividend rate is not maintained there is a high probability that even their jobs will be vacated, and by appointment.

The other question that remains to be considered is that of the method of arriving at technical decisions regarding matters pertaining to the physical equipment. If the telephone service is to be maintained there is an infinitely wider variety of things which cannot be done than there are of things which can be done. Electrical circuits are no respecter of persons, and if a circuit is dictated which is contrary to Ohm’s Law, or any of a dozen other fixed electrical relationships, it will not work even if the chief engineer himself requests it. It might with some justice be said that the greater part of one’s technical training in such positions consists in knowing what not to do, or, at least, what not to try. As long as telephone service is the final criterion, decisions as to which circuits shall be given preference are made, not by chief engineers, but by results of experiment. That circuit will be used which upon experiment gives the best results. A large part of technical knowledge consists in knowing on the basis of experiments already performed which of two things will work the better. In case such knowledge does not exist already it is a problem for the research staff, and not for the chief executive. The research staff discovers which mode of procedure is best, tries it out on a small scale until it is perfected, and designs similar equipment for large scale use. The chief executive sees that these designs are executed.

Such are some of the basic properties of any competent functional organization. It has no political precedents. It is neither democratic, autocratic, nor dictatorial. It is dictated by the requirements of the job that has to be done, and, judging from the number of human beings performing quietly within such organizations, it must also be in accord with the biological nature of the human animal.

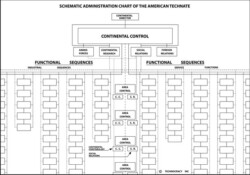

Organization Chart. On the basis of the foregoing, we are now prepared to design the social organization which is to accomplish the objectives enumerated above. This organization must embrace every socially useful function performed on the North American Continent, and its active membership will be composed of all the people performing such functions in that area. Since, as we have pointed out before, there does not exist in this area any sequence of functions which is independent of, or can be isolated from, the remaining functions, it follows that in order to obtain the highly necessary synchronization and co-ordination between all the various functions they must all pyramid to a common head.

The basic unit of this organization is the Functional Sequence. A Functional Sequence is one of the larger industrial or social units, the various parts of which are related one to the other in a direct functional sequence.

Thus, among the major Industrial Sequences we have transportation (railroads, waterways, airways, highways, and pipelines); communication (mail, telephone, telegraph, radio, and television); agriculture (farming, ranching, dairying, etc.); and the major industrial units such as textiles, iron, and steel, etc.

Among the Service Sequences are education (this would embrace the complete training of the younger generation), and public health (medicine, dentistry, public hygiene, and all hospitals and pharmaceutical plants as well as institutions.).

Due to the fact that no Functional Sequence is independent of other Functional Sequences, there is a considerable amount of arbitrariness in the location of the boundaries between adjacent Functional Sequences. Consequently, it is not possible to state a priori exactly what the number of Functional Sequences will be, because this number is itself arbitrary. It is possible to make each Sequence large, with a consequent decrease in the number required to embrace the whole social mechanism. On the other hand, if the sequences are divided into smaller units, the number will be correspondingly greater. It appears likely that the total number actually used will lie somewhere between 50 and 100. In an earlier layout the social mechanism was blocked into about 90 Functional Sequences, though future revision will probably change this number somewhat, plus or minus.

Figure 8 The schematic relationship showing how these various Functional Sequences pyramid to a head and are there coordinated is illustrated in Figure 8. At the bottom of the chart on either side are shown schematically several Functional Sequences. In the lower left-hand corner, there are shown five of the Industrial Sequences, and in the lower right-hand corner are five of the Service Sequences. In neither of these groups does the size of the chart allow all of the Functional Sequences to be shown. On a larger chart the additional Functional Sequences would be shown laterally in the same manner as those shown here. Likewise, each of the Functional Sequences would spread downward with its own internal organization chart, but that is an elaboration which does not concern us here.

Special Sequences. There are five other Sequences in this organization which are not in the class with the ordinary Functional Sequences that we have described. Among these is the Continental Research. The staffs described heretofore are primarily operating and maintenance staffs, whose jobs are primarily the maintaining of operation in the currently approved manner. In every separate Sequence, however, Service Sequences as well as Industrial Sequences, it is necessary, in order that stagnation may not develop, to maintain an alert and active research for the development of new processes, equipment and products. Also, there must be continuous research in the fundamental sciences—physics, chemistry, geology, biology, etc. There must likewise be continuous analysis of data and resources pertaining to the Continent as a whole, both for the purposes of coordinating current activity, and of determining longtime policies as regards probable growth curves in conjunction with resource limitation and the like.

The requirements of this job render it necessary that all research in whatever field be under the jurisdiction of a single research body, so that all research data are at all times available to all research investigators wishing to use them. This special relationship is shown graphically in the organization chart. The chief executive of this body, the Director of Research, is at the same time a member of the Continental Control, and also a member of the staff of the Continental Director.

On the other hand, branches of the Continental Research parallel laterally every Functional Sequence in the social mechanism. These bodies have the unique privilege of determining when and where any innovation in current methods shall be used. They have also the authority to cut in on any operating flow line for experimental purposes when necessary. In case new developments originate in the operating division, they still have to receive the approval of the Continental Research before they can be installed. In any Sequence a man with research capabilities may at any time be transferred from the operating staff to the research staff and vice versa.

Another all-pervading Sequence which is related to the remainder of the organization in a manner similar to that of Research is the Sequence of Social Relations. The nearest present counterpart is that of the judiciary. That is, its chief duty is looking after the ‘law and order,’ or seeing to it that everything as regards individual human relationships functions smoothly.

While the Sequence of Social Relations is quite similar to that of the present judiciary, its methods are entirely different. None of the outworn devices of the present legal profession, such as the sparring between scheming lawyers, or the conventional passing of judgment by ‘twelve good men and true’ would be allowed. Questions to be settled by this body would be investigated by the most impersonal and scientific methods available. As will be seen later, most of the activities engaging the present legal profession, namely litigation over property rights, will already have been eliminated.

Another of these special Sequences is the Armed Forces. The Armed Forces, as the name implies, embraces the ordinary military land, water, and air forces, but most important of all, it also includes the entire internal police force of the Continent, the Continental Constabulary. This latter organization has no precedent at the present time. At the present, the internal police force consists of the familiar hodge-podge of local municipal police, county sheriffs, state troopers, and various denominations of federal agents, most of the former being controlled by local political machines and racketeers. This Continental Constabulary, by way of contrast, is a single disciplined organization under one single jurisdiction. Every member of the Constabulary is subject to transfer from any part of the country to any other part on short notice.

While the Continental Constabulary is under the discipline of the Armed Forces, it receives its instructions and authorization for specific action from the Social Relations and Area Control.

This Sequence—the Area Control—is the coordinating body for the various Functional Sequences and social units operating in any one geographical area of one or more Regional Divisions. It operates directly under the Continental Control.

The Foreign Relations occupies a similar position, except that its concern is entirely with international relations. All matters pertaining to the relation of the North American Continent with the rest of the world are its domain. The personnel of all Functional Sequences will pyramid on the basis of ability to the head of each department within the Sequence, and the resultant general staff of each Sequence will be a part of the Continental Control. A government of function!

The Continental Control. The Continental Director, as the name implies, is the chief executive of the entire social mechanism. On his immediate staff are the Directors of the Armed Forces, the Foreign Relations, the Continental Research, and the Social Relations and Area Control.

Next downward in the sequence comes the Continental Control, composed of the Directors of the Armed Forces, Foreign Relations, Continental Research, Social Relations and Area Control, and also of each of the Functional Sequences. This superstructure has the last word in any matters pertaining to the social system of the North American Continent. It not only makes whatever decisions pertaining to the whole social mechanism that have to be made, but it also has to execute them, each Director in his own Sequence. This latter necessity, by way of contrast with present political legislative bodies, offers a serious curb upon foolish decisions.

So far nothing has been said specifically as to how vacancies are filled in each of these positions. It was intimated earlier that within the ranks of the various Functional Sequence jobs would be filled or vacated by appointment from above.

This still holds true for the position of Sequence Director. A vacancy in the post of Sequence Director must be filled by a member of the Sequence in which the vacancy occurs. The candidates to fill such position are nominated by the officers of the Sequence next in rank below the Sequence Director. The vacancy is filled by appointment by the Continental Control from among the men nominated.

The only exception to this procedure of appointment from above occurs in the case of the Continental Director due to the fact that there is no one higher. The Continental Director is chosen from among the members of the Continental Control by the Continental Control. Due to the fact that this Control is composed of only some 100 or so members, all of whom know each other well, there is no one better fitted to make this choice than they.

The tenure of office of every individual continues until retirement or death, unless ended by transfer to another position. The Continental Director is subject to recall on the basis of preferred charges by a two-thirds decision of the Continental Control. Aside from this, he continues in office until the normal age of retirement.

Similarly in matters of general policy he is the chief executive in fact as well as in title. His decisions can only be vetoed by two-thirds majority of the Continental Control.

It will be noted that the above is the design of a strong organization with complete authority to act. All philosophic concepts of human equality, democracy and political economy have upon examination been found totally lacking and unable to contribute any factors of design for a Continental technological control. The purpose of the organization is to operate the social mechanism of the North American Continent. It is designed along the lines that are incorporated into all functional organizations that exist at the present time. Its membership comprises the entire population of the North American Continent. Its physical assets with which to operate consist of all the resources and equipment of the same Area.

Regional Divisions. It will be recognized that such an organization as we have outlined is not only functional in its vertical alignment but is geographical in its extent. Some one or more of the Functional Sequences operates in every part of the Continent. This brings us to the matter of blocking off the Continent into administrative areas. For this purpose, various methods of geographical division are available. One would be to take the map of North America and amuse oneself by drawing irregularly shaped areas of all shapes and sizes, and then giving these names. The result would be equivalent to our present political subdivisions into nations, states or provinces, counties, townships, precincts, school districts, and the like—a completely unintelligible hodgepodge.

A second method, somewhat more rational than the first, would be to subdivide the Continent on the basis of natural geographical boundaries such as rivers, mountain ranges, etc., or else to use industrial boundaries such as mining regions, agricultural regions, etc. Both of these methods are objectionable because of the irregularity of the boundaries that would result, and also because there are no clean-cut natural or industrial boundaries in existence. The end-product, again, would be confusion.

A third alternative remains, that of adopting some completely arbitrary rational system of subdivisions such that all boundaries can be defined in a few words and that every subdivision can be designated by a number for purposes of simplicity of administration and of record keeping. For this purpose, no better system than our scientific system of universal latitude and longitude has ever been devised. Any point on the face of the earth can be accurately and unambiguously defined by two simple numbers, the latitude and longitude. Just as simply, areas can be blocked off by consecutive parallels of latitude and consecutive meridians.

It is the latter system of subdividing the Continent on the basis of latitude and longitude that we shall adopt.

By this system we shall define a Regional Division to be a quadrangle bounded by two successive degrees of longitude and two successive degrees of latitude. The number assigned to each Regional Division will be that of the combined longitude and latitude of the point at the southeast corner of the quadrangle. Thus, the Regional Division in which New York City is located is 7340; Cleveland, 8141; St. Louis, 9038; Chicago, 8741; Los Angeles, 11834; Mexico City, 9919; Edmonton, 11353, etc.

In this manner all the present political boundaries are dispensed with. The whole area is blocked off into a completely rational and simple system of Regional Division, the number for each of which not only designates it but also locates it.

It is these Regional Divisions that form the connecting link between the present provisional organization of Technocracy and the proposed operating one depicted in the foregoing chart. In the process of starting an organization the membership of a particular unit is much more likely to be united by geographic proximity than as members of any particular functional sequence. Accordingly, the provisional organization is of necessity, in the formative period, built and administered on a straight line basis where the individual administrative units are blocked off according to the Regional Divisions in which they happen to occur. As the organization evolves, the transition over into the functional form that we have outlined occurs spontaneously. Already the activities of the organization embrace education, publication, and public speaking, as well as research. As time goes on not only will these activities expand but other functions will be added. As fast as the membership in the Functional Sequences will allow, Sequences of Public Health, Transportation, Communication, etc., will be instituted. Even in this formative period a network of amateur short-wave radio stations between the various Regional Divisions is being built. None of these occur overnight, but as the organization evolves there will be an orderly transition over to administration along the functional lines as indicated.

Requirements. Now that we have sketched in outline the essential features of the social organization, there remains the problem of distribution of goods and services. Production will be maintained with a minimum of oscillation, or at a high load factor. The last stage in any industrial flow line is use or consumption. If in any industrial flow line an obstruction is allowed to develop at one point, it will slow down, and, if uncorrected, eventually shut down that entire flow line. This is no less true of the consumption stage than of any other stage. Present industrial shut down, for instance, has resulted entirely from a blocking of the flow line at the consumption end. If the production is to be non-oscillatory and maintained at a high level so as to provide a high standard of living, it follows that consumption must be kept equal to production, and that a system of distribution must be designed which will allow this. This system of distribution must do the following things:

- Register on a continuous 24-hour time period basis the total net conversion of energy, which would determine (a) the availability of energy for Continental plant construction and maintenance, (b) the amount of physical wealth available in the form of consumable goods and services for consumption by the total population during the balanced load period.

- By means of the registration of energy converted and consumed, make possible a balanced load.

- Provide a continuous 24-hour inventory of all production and consumption.

- Provide a specific registration of the type, kind, etc., of all goods and services, where produced, and where used.

- Provide specific registration of the consumption of each individual, plus a record and description of the individual.

- Allow the citizen the widest latitude of choice in consuming his individual share of Continental physical wealth.

- Distribute goods and services to every member of the population.

On the basis of these requirements, it is interesting to consider money as a possible medium of distribution. But before doing this, let us bear in mind precisely what the properties of money are. In the first place, money relationships are all based upon ‘value,’ which in turn is a function of scarcity. Hence, as we have pointed out previously, money is not a ‘measure’ of anything. Secondly, money is a debt claim against society, and is valid in the hands of any bearer. In other words, it is negotiable; it can be traded, stolen, given, or gambled away. Thirdly, money can be saved. Fourthly, money circulates, and is not destroyed or canceled out upon being spent. On each of these counts money fails to meet our requirements as our medium of distribution.

Suppose, for instance, that we attempted to distribute by means of money, the goods and services produced. Suppose that it were decided that 200 billion dollars’ worth of goods and services were to be produced in a given year, and suppose further that 200 billion dollars were distributed to the population during that time with which to purchase these goods and services. Immediately the foregoing properties of money would create trouble. Due to the fact that money is not a physical measure of goods and services, there is no assurance that the prices would not change during the year, and that 200 billion dollars at the end of the year would be adequate to purchase the goods and services it was supposed to purchase. Due to the fact that money can be saved, there is no assurance that the 200 billion dollars issued for use in a given year would be used in that year, and if it were not used this would immediately begin to curtail production and to start oscillations. Due to the fact that money is negotiable, and that certain human beings, by hook or crook, have a facility for getting it away from other human beings, this would defeat the requirement that distribution must reach all human beings. A further consequence of the negotiability of money is that it can be used very effectively for purposes of bribery. Hence the most successful accumulators of money would be able eventually not only to disrupt the flow line, but also to buy a controlling interest in the social mechanism itself, which brings us right back to where we started from. Due to the fact that money is a species of debt, and hence cumulative, the amount would have to be continuously increased, which, in conjunction with its property of being negotiable, would lead inevitably to concentration of control in a few hands, and to general disruption of the distribution system which was supposed to be maintained.

Thus, money, in any form whatsoever, is completely inadequate as a medium of distribution in an economy of abundance. Any social system employing commodity evaluation (commodity valuations are the basis of all money) is a Price System. Hence it is not possible to maintain an adequate distribution system in an economy of abundance with a Price System control.

The Mechanism of Distribution. We have already enumerated the operating characteristics that a satisfactory mechanism of distribution must possess, and we have found that a monetary mechanism fails signally on every count. A mechanism possessing the properties we have enumerated, however, is to be found in the physical cost of production—the energy degraded in the production of goods and services.

In earlier lessons we discussed in some detail the properties of energy, together with the thermodynamic laws in accordance with which energy transformations take place. We found that, for every movement of matter on the face of the earth, a unidirectional degradation of energy takes place, and that it was this energy loss incurred in the production of goods and services that, in the last analysis, constitutes physical cost of production. This energy, as we have seen, can be stated in invariable units of measurements—units of work such as the erg or the kilowatt-hour, or units of heat such as the kilogram-calorie or the British thermal unit. It is therefore possible to measure with a high degree of precision the energy cost of any given industrial process, or for that matter the energy cost of operating a human being. This energy cost is not only a common denominator of all goods and services, but a physical measure as well, and it has no value connotations whatsoever.

The energy cost of producing a given item can be changed only by changing the process. Thus, the energy cost of propelling a Ford car a distance of 15 miles is approximately the energy contained in one gallon of gasoline. If the motor is in excellent condition somewhat less than a gallon of gasoline will suffice, hence the energy cost is lower. On the other hand, if the valves become worn and the pistons become loose, somewhat more than a gallon of gasoline may be required and the energy cost increases. A gallon of gasoline of the same grade always contains the same amount of energy.

In an exactly similar manner energy derived from coal or water power is required to drive factories, hence the energy cost of the product would be the total amount of energy consumed in a given time divided by the total number of products produced in that time. Energy, likewise, is required to operate the railroads, telephones, telegraphs, and radio. It is required to drive agricultural machinery and to produce the food that we consume. Everything that moves does so only with a corresponding transformation of energy.

Now suppose that the Continental Control, after taking into due account the amount of equipment on hand, the amount of new construction of roads, plant, etc., required for the needs of the population, and the availability of energy resources, decides that for the next two years the social mechanism can afford to expend a certain maximum amount of energy (equivalent to that contained in a given number of millions of tons of coal). This energy can be allocated according to the uses to which it is to be put. The amount required for new plant, including roads, houses, hospitals, schools, etc., and for local transportation and communication will be deducted from the total as a sort of overhead, and not chargeable to individuals. After all of these deductions are made, including that required for the education and care of children and the maintenance of hospitals and public institutions generally, the remainder will be devoted to the production of goods and services to be consumed by the adult public-at-large.

Suppose, next, that a system of record-keeping be instituted, whereby a consuming power be granted to this adult public-at-large in an amount exactly equal to this net remainder of energy available for the producing of goods and services to be consumed by this group. This equality can only be accomplished by stating the consuming power itself in denominations of energy. Thus, if there be available the means of producing goods and services at an expenditure of 100,000 kilogram calories per each person per day, each person would be granted an income, or consuming power, at a rate of 100,000 kilogram calories per day.

Income. Now let us see what further details will have to be incorporated in this distributive system in order to satisfy the requirements we have laid down. First, let us remember that this income is usable for the obtaining of consumers’ goods and services, and not for the purchase of articles of value. That being the case, there is a fairly definite limit to how many goods and services a single individual can consume, bearing in mind the fact that he only lives 24 hours a day, one-third of which he sleeps, and a considerable part of the remainder of which he works, loafs, plays, or indulges in other pursuits many of which do not involve a great physical consumption of goods.

Let us recall that every individual in the society must be supplied, young and old alike. Since it is possible to set arbitrarily the rate of production at a quite high figure, it is entirely likely that the average potential consuming power per adult can be set higher than the average adult’s rate of physical consumption. Since this is so, there is no point in introducing a differentiation in adult incomes in a manner characteristic of economies of scarcity. From the point of view of simplicity of record-keeping, moreover, enormous simplification can be effected by making all adult incomes male and female, alike, equal. Thus, all would receive a large income, quite probably larger than they would find it convenient to spend. This income would continue without interruption until the death of the recipient. The working period, however, after the period of transition would probably not need to exceed the 20 years from the age of 25 to 45, on the part of each individual.

Still further properties that must be incorporated into this energy income received by individuals are that it must be non-negotiable and non-savable. That is, it must be valid only in the hands of the person to whom issued, and in no circumstances transferable to any other individual. Likewise, since it is issued on the basis of a budget expenditure covering two years, it must only be valid for that two-year period, and null and void thereafter. Otherwise, it would be saved in part, and serve to completely upset the balance in the operating load in future periods. On the other hand, there is no need for saving, because an income and social security is already guaranteed independently to each individual until death.

The reason for taking two years as the balanced-load period of operation of the social mechanism is a technological one. The complete industrial cycle for the whole North American Continent, including the growing period of tropical plants, such as Cuban sugar cane, is somewhat more than one year. Hence a two-year period is taken as the nearest integral number of years to this industrial cycle. All operating plans and budgets would thus be made on a two-year basis, and at the end of that time the books would be balanced and closed for that period. No debts would be possible, and the current habit of mortgaging the future to pay for present activities would be completely eliminated.

If, as is quite likely, the public find it inconvenient to consume all their allotted energy for that time period the unspent portion of their allotment will merely be canceled at the end of the period. The saving will be effected by society rather than by the individual, and the energy thus saved, or the goods and services not consumed, will be carried over into the next balanced load period. This will not, as will be amplified later, throw the productive system into oscillation, because production will always be geared to the rate of consumption, and not to the total energy allotment. In other words, if for a given balanced load period the total energy allotment be equivalent to that contained in, say four billion tons of coal, this merely means that we are prepared if need be, to burn four billion tons of coal, and distribute the resultant goods and services during that time period. This merely sets a maximum beyond which consumption for that time period will not be allowed to go. If the public, however, finds it inconvenient to consume that amount of goods and services, and actually consumes only an amount requiring three billion tons of coal to produce, production will be curtailed by that amount, and the extra billion tons of coal will not be used, but will remain in the ground until needed.

Energy Certificates. There are a large number of different bookkeeping devices whereby the distribution to, and records of rate of consumption of the entire population can be kept. Under a technological administration of abundance, there is only one efficient method—that employing a system of Energy Certificates. By this system, all books and records pertaining to consumption are kept by the Distribution Sequence of the social mechanism. The income is granted to the public in the form of energy certificates.

These certificates are merely pieces of paper containing certain printed matter. They are issued individually to every adult of the entire population. The certificates issued to an individual may be thought of as possessing some of the properties both of bank check and of a traveler’s check. They would resemble a bank check in that they carry no face denomination. They receive their denomination only when being spent. They resemble a traveler’s check in that they possess some means of ready identification, such as counter-signature, photograph, or some similar device, so as to establish easy identification by the person to whom issued, and at the same time remain absolutely useless in the hands of anyone else.

The record of one’s income and its rate of expenditure is kept by the Distribution Sequence, so that it is a simple matter at any time for the Distribution Sequence to ascertain the state of an unknown customer’s balance. This is somewhat analogous to a combination bank and department store, wherein all the customers of the store also keep bank accounts at the store bank. In such a case the customer’s credit at the department store is as good as his bank account, and the state of this account is available to the store at all times.

Besides the properties enumerated above, our Energy Certificates also contain the following additional information about the person to whom issued:

The background color of the certificate records whether he has not yet begun his period of service, is now performing service, or is retired, a different color being used for each of these categories. A diagonal stripe in one direction records that the purchaser is of the male sex; a corresponding diagonal in the other direction signifies the female sex. In the background across the face of the certificate is printed or water-marked the two-year balanced load period, say 1936-37, during which the particular certificate is valid. Also printed on the certificate is additional data about the recipient, including the geographical area in which he resides, and a catalogue number, signifying the specific Functional Sequence and job at which he works.

When making purchases of either goods or services an individual surrenders the energy certificates properly identified and signed. These surrendered certificates are then perforated with a catalogue numbers of the specific item and amount purchased, and also its energy cost. These canceled certificates then clear through the bookkeeping apparatus of the Distribution Sequence.

The significance of this, from the point of view of knowledge of what is going on in the social system, and of social control, can best be appreciated when one surveys the whole system in perspective. First, one single organization is manning and operating the whole social mechanism. This same organization not only produces but distributes all goods and services. Hence a uniform system of record-keeping exists for the entire social operation, and all records of production and distribution clear to one central headquarters. Tabulation of the information contained on the canceled Energy Certificates day by day provides a complete record of distribution, or of the public rate of consumption by commodity, by sex, by regional division, by occupation, and by age group.

With this information clearing continuously to a central headquarters we have a case exactly analogous to the control panel of a power plant, or the bridge of an ocean liner, or the meter panel of a modern airplane. In the case of a steam plant the meter panel records continuously the steam pressure of the boilers, the fuel record, the voltage and kilowatt output of the generators, and all other similar pertinent data. In the case of operating an entire social mechanism the data required are more voluminous in detail, but not otherwise essentially different from that provided by the instrument panel in the steam plant.

The clearing of the Energy Certificates, tabulated in all the various ways we have indicated, gives precise information at all times on the state of consumption of every kind of commodity or service in all parts of the Continent. In addition to this there is also corresponding information on stocks of materials and rates of operation in every stage of every industrial flow line. There is, likewise, a complete record on all hospitals, on the educational system, amusements, and others on the more purely social services. This information makes it possible to know exactly what to do at all times in order to maintain the operation of the social mechanism at the highest possible load factor and efficiency.

A Technocracy. The end products attained by a high-energy social mechanism on the North American Continent will be:

- a high physical standard of living,

- a high standard of

- public health,

- a minimum of unnecessary labor,

- a minimum of wastage of non-replaceable resources,

- an educational system to train the entire younger generation indiscriminately as regards all considerations other than inherent ability—a Continental system of human conditioning.

The achievement of these ends will result from a centralized control with a social organization built along functional lines, similar to that of the operating force of any large functional unit of the present such as the telephone system or the power system.

Non-oscillatory operation at high load factor demands not only functional organization of society but a mechanism of distribution that will:

- Insure a continuous distribution of goods and services to every member of the population;

- enable all goods and services to be measured in a common physical denominator;

- allow the standard of living for the whole of society to be arbitrarily set as an independent variable, and

- insure continuous balance between production and consumption.

Such a mechanism is to be found in the physical cost of production, namely, the energy degradation in the production of goods and services. Incomes can be granted in denominations of energy in such a manner that they cannot be lost, saved, stolen, or given away. All adult incomes are to be made equal, though probably larger than the average ability to consume. Such an organization has no precedence in any of the political forms. It is neither a democracy, an aristocracy, a plutocracy, a dictatorship, nor any of the other familiar political forms, all of which are completely inadequate and incompetent to handle the job. It is, instead, a Technocracy, being built along the technological lines of the job in hand.

For further discussion of distribution refer to the official pamphlet, The Energy Certificate.